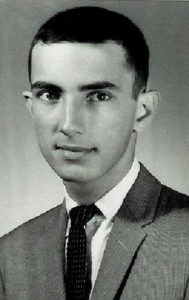

When I was in the eighth grade, filled with idealism and a strong belief in God, I sensed a calling to become a Catholic priest. Such was common for parochial school boys in the 1950’s. Almost every order of priests had “minor seminaries” in which qualified boys with some sense of initial calling were encouraged to enroll for high school. I never felt the least pressure from my parents; but, as was the common attitude of the time, it was a great honor to have a son who was a priest. I enrolled in the Franco-American minor seminary of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate; and on Labor Day weekend 1958 my family drove me from our home in Rhode Island to Bucksport, Maine.

Although they hardly exist anymore – thank God – minor seminaries were very common in 1950’s and 60’s. Such institutions began to flourish in the sixteenth century under the assumption that it was good to take boys early to properly train them intellectually, morally and spiritually for the priesthood. The training and schedule were still virtually the same in the twentieth century. As a high-school seminarian, a loud bell in an open dormitory room of twenty to forty students awakened me at 6:15 each morning. No talking was ever permitted in the dormitory. After washing our hand and faces we went to the chapel for morning prayers, followed by a short sermon, daily mass, and breakfast – again all in silence.

Almost every moment of every day was regulated, even the language we spoke – French until supper and English thereafter. We could only ever leave the campus with permission and only for a good reason. We were warned not to socialize with girls before we left for the Christmas vacation and before the long summer break. I dutifully obeyed. It all certainly made for developing discipline in one’s life as well as for very good study habits, though not for good psychosexual development. More than half who began as freshman dropped out by the end of sophomore year.

An example of just how much we lived in an isolated, self-contained world is that we began daylight saving time one week before the rest of the country so that we could play softball during the recreation hour between supper and the evening study period. Of course, sports were mandatory for everyone.

For whatever reasons I thrived in Bucksport. I liked the camaraderie and the sports; and I did well academically. My sense of calling to become a priest deepened throughout high school. I was happy that I was where I belonged. In retrospect, I was also very innocent, naïve, and stunted in my emotional development. At any rate I applied and was accepted to continue on to the junior college seminary in Bar Harbor, Maine.

The junior college seminary was less structured and restrictive than the high school seminary. My spiritual life while at Bucksport, Bar Harbor, and the next year at the novitiate in Colebrook, New Hampshire was very conventional for the time. I don’t remember myself being particularly pious; but I believed in the presence of Jesus in the Eucharist; and I attended daily Mass as the high point of each day. I prayed, meditated as counseled, studied, and my sense calling to become a priest continued to deepen. I could imagine no greater vocation than to serve God and the Church. I believed; and I wanted to continue to the next step towards the priesthood and “religious life,” i.e., the life within my chosen religious community, by taking vows of poverty, chastity\celibacy, and obedience.

The junior college seminary was less structured and restrictive than the high school seminary. My spiritual life while at Bucksport, Bar Harbor, and the next year at the novitiate in Colebrook, New Hampshire was very conventional for the time. I don’t remember myself being particularly pious; but I believed in the presence of Jesus in the Eucharist; and I attended daily Mass as the high point of each day. I prayed, meditated as counseled, studied, and my sense calling to become a priest continued to deepen. I could imagine no greater vocation than to serve God and the Church. I believed; and I wanted to continue to the next step towards the priesthood and “religious life,” i.e., the life within my chosen religious community, by taking vows of poverty, chastity\celibacy, and obedience.

I internalized my vow of poverty from the beginning. Throughout my life I have wanted little and sought to live simply. That lifestyle certainly transitioned well into the second phase of my spiritual journey with its environmental dimension. I don’t remember if I ever believed that my religious superior’s voice was an expression of the will of God. I know that during my thirty years of religious life I was never really ever tested in my vow of obedience by being asked to do something I fully didn’t want to do. The vow of chastity\celibacy had a more complicated history that I describe further on.

When I took my temporary vows on August 2, 1965 I became a member of my religious order, the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. On that day it was announced that I would go to the major seminary in Rome for presumably the next seven years to study philosophy and theology after which I would be ordained.

It was very exciting arriving in Rome in the fall of 1965. It was the last session of the Second Vatican Council, a gathering during which all Catholic bishops in the world decide any and all matters of the Church. There is on average one such council every 100 years. In short and at the risk of oversimplifying, the Council had been called to modernize the Church and to welcome those aspects of the modern world that were compatible with the gospel. It was a time of great hope. However, in the giddy aftermath of the Council, combined with the cultural atmosphere of the late 1960’s, a time of upheaval ensued in the Church. Seminarians and priests left in great numbers. After centuries of suppression, the pendulum in the seminary swung in the opposite direction. I tell people that my seminary experience began in total suppression and ended it in total anarchy.

Arriving in Rome at the age 21 to begin my junior college year, I became a fulltime philosophy student for two years after which I would do an additional year to obtain a graduate degree. I studied at the Angelicum University, which taught the thirteenth century philosophy of Saint Thomas Aquinas, a beautifully built edifice of impeccable logic but, in my judgment, built on sand. Studying mostly thirteenth philosophy was a disappointing waste.

I asked my seminary superior not to do a third year of philosophy; but he would hear none of it. He informed me that all philosophy students who came to Rome continued on to a post-graduate degree in philosophy. It led to my first vocational crisis. At the beginning of 1968 during my third year of philosophy I announced that I needed time off; and I was granted permission to live with the Oblate priests who staffed the parish in International Falls, Minnesota. I taught the seventh and eighth grade in the parochial school for a year.

Before leaving Rome in the spring of 1968, I experienced a turning point in my attitude towards the teaching authority of the Church. To that point I had always reverentially deferred to my elders who were more experienced and learned than me. That all changed in 1968 when Pope Paul VI could not find a way out of the morass of condemning artificial contraception in the sexual act between husband and wife. His encyclical reaffirmed the teaching of his predecessor. As a seminarian I carefully read the pope’s encyclical at the end of which I muttered something to the effect, “No matter how many learned theological distinctions one makes against the morality of artificial birth control, if the conclusion lacks common sense, it’s bullshit.”

After returning to the States later that spring and in the years immediate following, various priests were silenced for stating their own personal conclusions about birth control. Sometimes they were even publicly reprimanded by their bishops who supported the pope. What I began to learn and became more convinced of with time is that the first and most important quality to becoming a bishop is loyalty to the institution and the pope. I know I never wanted a position of authority in my religious community or in the wider Church; and I already knew that loyalty to the institution and the pope were not my strong suit.

After teaching for a year in Minnesota I felt renewed in my calling to become a priest and was ready to begin my theological studies. My US Provincial Superior granted me permission to do my theological studies in San Antonio instead of Rome. Some of what I learned in theology made me question but never lose my faith. For example, in studying the New Testament gospels, I learned that there were three periods of development in the writing of each gospel. The first was what Jesus actually said and did, i.e., from approximately 0 to 30 AD. The second was what the early church, in its oral tradition, taught what Jesus said and did, i.e., from approximately 30 to 60 AD. The third period was what each gospel writer, with his own goal and audience in mind, wrote about what Jesus said and did, i.e., from approximately 60 to 100 AD. By the end of the course I wondered, “Who was the real Jesus? ” It didn’t shake my faith because I believed that Jesus was fully God and fully man.

Because spirituality and sexuality are oftentimes so central in our lives, I think they are intimately connected even when the connection is not apparent to us. When I took my temporary vow of chastity, i.e., celibacy, at the age of 20, I agreed with what my novice master had taught me and the other novices. I had never masturbated. I was still a virgin. Probably a combination of loneliness, the culture of the late 1960’s and beyond, more critical thinking on my part about celibacy, the sexual drive, “love” and rationalization all came together so that I had four sexual experiences while in the major seminary and later as a priest – from a one-time, immediately regretted occurrence to a relationship that lasted over a year and for which I felt no guilt until months after it ended.

I make absolutely no excuse for my sexual behavior. At the same time I know enough first and secondhand stories of other seminarians and priests to know that that my story was not unique. I think my peers and I all took a vow of chastity, expecting to be always faithful to it. But no matter how much religious fervor, zeal, and determination one has when taking such a vow, things change.

At some point, I decided that I needed to be faithful to the vow of chastity\celibacy that I had taken even though I no longer subscribed to the teaching I had learned. Its spiritual meaning and value in my life were only that I be authentic and honest with myself about the public vow I had taken. The vow had become a cross to bear so that I could continue doing the ministry, which I judged important and which was so meaningful to me. I realize that the “experience of the cross” such as suffering and a continuous difficult situation in life can become an integral part of one’s spiritual journey; but if I integrated celibacy in that way, that integration was a minor part of my spirituality because I have no recollection of it.

As an aside, the life of a Catholic priest is at least solitary if not also lonely. In our information age during which sexual crimes and scandals of the Catholic clergy have become public knowledge, I think that instead of being a shining star in the Church’s crown, celibacy has become a blot. Mandatory celibacy is unenforceable. It’s obviously for the Church to decide whether accepting only males who are willing to make such a vow is in the Church’s best interest and whether requiring such a vow is unfair to those for whom making the vow is psychologically and\or spiritually a bad choice. Given my obedience to not socialize with girls during my high school and junior college winter and summer vacation periods, I know that in retrospect my vow of chastity was an immature and an unhealthy psychological and spiritual choice for me and, I suspect, for most of my peers.

I began first grade in September 1950 at Saint Mathieu’s parochial school, which was taught entirely by the Sisters of Saint Anne, a community of nuns founded in the Province of Quebec. During the morning all the classes were taught in English. During the afternoon, all classes were in French. At church the Sunday masses were in Latin with the sermon and announcements being in French. Our boy scout troop was parish-based as well as the summer camp my brothers and I attended during the first two weeks of July. In the fourth grade I became an altar boy. By the seventh grade I regularly attended daily mass and the evening church devotions during the month of Mary (May) and the month of the Rosary (October).

I began first grade in September 1950 at Saint Mathieu’s parochial school, which was taught entirely by the Sisters of Saint Anne, a community of nuns founded in the Province of Quebec. During the morning all the classes were taught in English. During the afternoon, all classes were in French. At church the Sunday masses were in Latin with the sermon and announcements being in French. Our boy scout troop was parish-based as well as the summer camp my brothers and I attended during the first two weeks of July. In the fourth grade I became an altar boy. By the seventh grade I regularly attended daily mass and the evening church devotions during the month of Mary (May) and the month of the Rosary (October). The junior college seminary was less structured and restrictive than the high school seminary. My spiritual life while at Bucksport, Bar Harbor, and the next year at the novitiate in Colebrook, New Hampshire was very conventional for the time. I don’t remember myself being particularly pious; but I believed in the presence of Jesus in the Eucharist; and I attended daily Mass as the high point of each day. I prayed, meditated as counseled, studied, and my sense calling to become a priest continued to deepen. I could imagine no greater vocation than to serve God and the Church. I believed; and I wanted to continue to the next step towards the priesthood and “religious life,” i.e., the life within my chosen religious community, by taking vows of poverty, chastity\celibacy, and obedience.

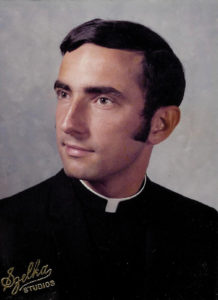

The junior college seminary was less structured and restrictive than the high school seminary. My spiritual life while at Bucksport, Bar Harbor, and the next year at the novitiate in Colebrook, New Hampshire was very conventional for the time. I don’t remember myself being particularly pious; but I believed in the presence of Jesus in the Eucharist; and I attended daily Mass as the high point of each day. I prayed, meditated as counseled, studied, and my sense calling to become a priest continued to deepen. I could imagine no greater vocation than to serve God and the Church. I believed; and I wanted to continue to the next step towards the priesthood and “religious life,” i.e., the life within my chosen religious community, by taking vows of poverty, chastity\celibacy, and obedience. I was ordained as a priest in 1972. My spirituality during my years in the major seminary and the priesthood was very Christocentric, i.e., Jesus centered. He was my model and teacher. He was at the center of my prayer life. When I celebrated Mass, I celebrated his presence in the church community. Jesus was at the center of my experience of God. A New Testament text was usually my starting point of any discursive meditation.

I was ordained as a priest in 1972. My spirituality during my years in the major seminary and the priesthood was very Christocentric, i.e., Jesus centered. He was my model and teacher. He was at the center of my prayer life. When I celebrated Mass, I celebrated his presence in the church community. Jesus was at the center of my experience of God. A New Testament text was usually my starting point of any discursive meditation. After decades of stunted growth in my psycho-sexual development I learned how to relate to women on all levels. I had three consecutive partnerships that eventually ended. Five months after meeting Karen I knew for sure that I had struck gold and that I could live a happy marriage with her. We married nine months later and have enjoyed wonderful years together on many levels. She has been the greatest gift in my life. Now, as we deal with my cancer, our love and communication deepen in a different way as we share our common and different thoughts and feelings about the present and the future. I now also experience her love as she physically cares for me. My biggest regret in dying is that I will leave Karen behind and be the cause of her grief.

After decades of stunted growth in my psycho-sexual development I learned how to relate to women on all levels. I had three consecutive partnerships that eventually ended. Five months after meeting Karen I knew for sure that I had struck gold and that I could live a happy marriage with her. We married nine months later and have enjoyed wonderful years together on many levels. She has been the greatest gift in my life. Now, as we deal with my cancer, our love and communication deepen in a different way as we share our common and different thoughts and feelings about the present and the future. I now also experience her love as she physically cares for me. My biggest regret in dying is that I will leave Karen behind and be the cause of her grief. In 1993 my then partner and I adopted an old wether (a castrated male goat). Woody became much more than a pet. He increasingly touched my soul during his three years with us. I became much more aware of what united rather than what divided us. I began experiencing him as my brother. Twenty-four years later I still refer to him as “my brother Woody.” He concretized for me like no other previous experience that we are all indeed one. I first experienced through Woody that all living beings are my brothers and sisters and cousins.

In 1993 my then partner and I adopted an old wether (a castrated male goat). Woody became much more than a pet. He increasingly touched my soul during his three years with us. I became much more aware of what united rather than what divided us. I began experiencing him as my brother. Twenty-four years later I still refer to him as “my brother Woody.” He concretized for me like no other previous experience that we are all indeed one. I first experienced through Woody that all living beings are my brothers and sisters and cousins. The personal conclusion I have reached is that death is final and that my existence will end. The cremated remains of my body will return to the earth as compounds and minerals. I have sought but found no credible alternative to the finality of death. On the other hand, none of us know for sure what happens after death. We may think we know; we may believe; we may hope; but none of us know. If my conclusion is wrong, I hope to be pleasantly surprised.

The personal conclusion I have reached is that death is final and that my existence will end. The cremated remains of my body will return to the earth as compounds and minerals. I have sought but found no credible alternative to the finality of death. On the other hand, none of us know for sure what happens after death. We may think we know; we may believe; we may hope; but none of us know. If my conclusion is wrong, I hope to be pleasantly surprised.